Do Elephants, Chimpanzees, and

Dolphins Think?

(Reflections on an Unfortunate

Paradigm Shift in

Ethology)

A Talk Given at the 30th

International Ethological Conference, August 18, 2007, Halifax, Nova Scotia,

Canada

Moti & Donna

Nissani

Department of

Interdisciplinary Studies, Wayne State University, Michigan,

USA

Contact us:

aa1674@wayne.edu

Some of the articles—and many photos of

chimpanzees, elephants, and dolphins—can be found in: www.is.wayne.edu/mnissani/

Abstract: A common tripartite classification of

the roots of animal behavior traces a particular behavior directly to one’s

genes, to equally mindless trial-and-error learning, or to thinking. Extant experimental lines of attack on

the problem of demarcating thoughtful actions from other types of actions are

briefly reviewed, paying special attention to widespread verificationist

approaches and to the nearly-forgotten Fabre’s and Thorndike’s falsificationist

methodologies. We

then review some of our own experimental applications of the falsificationist

approach to elephants, chimpanzees, and bottlenose dolphins. We propose similar, concrete,

applications of falsificationist experimental designs to claims of thinking in

corvids, apes, and other animals.

As long as we fail to apply falsificationist methodologies, Fabre’s claim

that we all too often try to “exalt animals” instead of objectively studying

them will remain as relevant today as it had been over a century ago. Finally, even if all non-human animals

lack consciousness, self-awareness, theory of mind, and thinking, we argue that

ecology, aesthetics, ethics, kinship, human borderline consciousness, and limits

to what science can know all suggest that animals deserve a far more prominent

place in our moral compass than they enjoy now.

The questions we wish to

ask: Can animals of some species

think? Solve problems in their

head? (not just blindly try everything?)

Have a concept of self? Are

animals conscious?

These are probably interrelated

aspects of the same underlying neural circuitry, but here we shall just focus on

one aspect of this complex equation:

thinking. We’ll make use of

Marian Dawkins’ reflections (1993,

Through Our Eyes Only, p. 97):

A possible definition of what we mean by thinking is not

only having internal representation of the world but that it should be able to

perform some sort of internal manipulation of that representation—working out

what would happen if one element were changed, for instance—and behaving

appropriately according to its changed presentation. Thinking is therefore most likely to

occur in animals where working out in advance what the best course of action

might be is a great deal quicker and safer than trying each one in turn and

seeing which one is best in practice.

If all an animal can do is to follow a set of rules, then there is no

reason to suspect it has a mind—that it can “think.”

Two misconceptions must be first

be dealt with:

Misconception

#1: Thinking

confers great evolutionary advantage by allowing an animal to read other minds

and solve problems in one’s own mind without trying everything through blind

trial and error. But these

advantages are perhaps more than counterbalanced by:

a.

The most successful species,

e.g., E. coli, fruit flies, probably do not think.

b.

The brain is expensive to

develop and maintain (cf., for example, Paul R. Manger, 2006,

Biol. Rev., 81:

293–338). These costs alone might outweigh any

potential benefit.

c.

Thinking often involves an

appreciation for complexity and uncertainty, and hence may lead to fumbling and

hesitation in critical situations (that is one reason why organizations like the

Iranian Revolutionary Guards and the U.S. Marines work so hard to eradicate

thinking).

d.

The only species that is

demonstrably capable of thinking and consciousness is very young (<2 millions

years?). Going by this one

exemplar, it would appear that the kind of thinking that evolution seems capable

of producing (feeble, intermittent, conformist, self-centered, narrow in scope)

could well be a recipe for extinction.

Misconception

#2: Animals deserve our love, our

compassion, our moral consideration, only if they think. We emphatically reject this narrow

view. We cannot take this issue up

here, and instead we’ll merely support our objections with one quotation

(R. D. Rosen, 2007, A Buffalo in the House, p.

200):

He had been

around a long time and he hadn’t met

many men who could understand the great but fragile web we were all part

of and wanted to help keep it together.

What Roger felt was that there had to be a better America than this

one. And maybe it was that hope

that helped explain his love for the crippled beast, this symbolic survivor of

nineteenth-century America, in the back of his horse trailer. It was animals who kept men honest. No amount of money or flattery—or even

carrots—could get an animal to be untrue to itself. The ground on which humans, which were

part animal, met animals, more human than we know, was sacred. Animals taught us to love even when we

couldn’t know whether we are loved back.

It was there, in an animal’s heartbeat, that we could feel the pulse of

something bigger than we were.

There, on that ground, we could feel the pulse of something bigger than

we were. There, on that ground, we

could feel that we were a part of nature, not apart from it. Roger flashed on the situation in

Yellowstone again. He knew that a

man who didn’t treat an animal with respect not only had no respect for nature;

he had no respect for himself.

The little-recognized Henri

Fabre (a working class Frenchman with too many principles and too few

connections, but nonetheless, in a fairer world, a serious contender to the

title of “father of ethology”, e.g., <1915, The Hunting Wasps. Read Fabre’s works, then read Lorenz’s, and judge for yourself!)

provided beautiful, solid, numerous observational refutations of the then

near-universal belief that insects think.

In one case, Fabre concluded “to understand that she [digger wasp] can

take a leg instead of an antenna is utterly beyond her powers.” The actions of insects.

are like a

series of echoes each awakening the next in a settled order, which allows none

to sound until the previous one has sounded. What a gulf separate intelligence and

instinct!

A few decades later, a

similarly powerful inference about the lack of the “power of rationality” in

animals emerged from E. L. Thorndike’s (1911, Animal Intelligence)

observations on chicks, cats, and dogs. For instance, cats learn to escape from

a puzzle box gradually, suggesting a stamping in of the association between the

stimulus and successful response, not causal reasoning. On the whole, Thorndike’s general

conclusions about the mentality of chicks, cats, and dogs seem to have stood the

test of time. For instance, in a

recent study, dogs learned to pull on a string to obtain food, but they did not

seem to understand the means-end connections of string-pulling tasks (Osthaus,

Lea, & Slater, 2004, Animal Cognition, 8:37-47). Thorndike said:

Most of the books [on animal psychology]

do not give us a psychology, but rather a eulogy of animals. They have all been about animal

intelligence, never about animal stupidity.” Human are eager to find

intelligence in animals.

Our plea is twofold:

1. We need,

indeed, to allow publication of a catalog of animal stupidities. Ethologists, and the scientific

community as a whole, should have in mind both seemingly intelligent—and

seemingly unintelligent—exemplars before deciding the issue of animal cognition.

We can find such examples

everywhere, once we start looking for them.

2. Before attributing intelligence to a particular

behavior, we must try harder to rule out the possibility that this behavior is

solely traceable to genetics, trial-and-error learning, and the interaction

between them (this is a variation of Morgan’s rule: the point here not to automatically take

a minimalist approach, but to try to experimentally disprove thinking).

àWe shall give a few examples of this latter approach in the rest of this presentation.

String-pulling in ravens and

elephants

We have done this with elephants (Nissani, 2004,

in: Comparative Vertebrate Cognition. Rogers, LJ, Kaplan G, editors,

pp 227-261), using a bungee cord.

Like the ravens, elephants have mastered the task well: video. At this point, we (and everyone else

that saw this) felt that we have proven that elephants are capable of insightful

behavior.

We then applied Fabre’s approach. In one case, we have tied the end of the

cord to a post (instead of placing it on the ground). Conceptually, the two tasks are

identical. But with this minor

discrepancy in the setup, our insightful elephants suddenly turned into a

fumbling elephant! We concluded that in the elephant’s

case—and perhaps also (an experiment worth doing!) in Heinrich’s more famous

case involving ravens—no insight was involved (Video)

Wanda, formerly of the Detroit Zoo,

readily mastered the string-pulling task (through a coordinated action of trunk

and foot or trunk and mouth)—until the string was tied to a

post.

àHere is a testable prediction: Heinrich's ravens, like our elephants, will NOT pass a similar

transfer task (and if so, their string-pulling is not

insightful)

Do animals know

that people see?

We applied Povinelli’s ingenious falsficationist

paradigm to 6 chimpanzees and some 20+ elephants, with numerous variations and

rigorous controls. We faced a

methodological problem involving the poor visual acuity of elephants. Most likely though, we find that Povinelli’s claim of 50% rate is almost certainly mistaken

in some of his own variations, and that in both species, in some tasks,

performance is roughly at the 70% level.

This is statistically significant but, in our view, Povinelli’s main

conclusion still stands (Nissani, 2004, in: Comparative Vertebrate

Cognition. Rogers, LJ, Kaplan G, editors, pp 227-261). The data are most consistent with an

acquired trial-and-error preference to interact with a human who faces you as

opposed to a human who doesn’t. One

has to see a chimpanzee, or an elephant, hesitating, looking intently at a

person who has her head covered with a bucket and a person with a bucket on her

shoulder, and then begging from the person who cannot see them, to come around

to this view. (That was the point

when one of us changed his mind about animal cognition, seeing our brightest

chimpanzee doing this). (Video)

Do

elephants know that people see? In

the buckets task, our chimpanzees performed at chance level, while elephants

chose the seeing person in 58%-78% of the cases. In this trial, the elephant is begging

from the person who could not see her.

Lifting a lid off a bucket and retrieving a

reward

Our next example comes from the simple maneuver of

lifting a lid off a bucket to get a reward inside the bucket. Now, an elephant can be taught to do

this well in some 30-60 minutes. It

looks like this: video

But what happens if you now place the treat inside the

bucket, as before, and the lid alongside the bucket, on the ground? Will the elephant behave as Fabre’s

digging wasps and pine moths? It

sure does (Nissani, 2006, J .Exp Psych: Anim Behav Proc, 31:91-96): video

After an elephant learned to lift a lid

to retrieve food from a bucket, the lid was placed alongside the bucket while

the food was simultaneously placed inside the bucket. All elephants continued to toss the lid

before retrieving the reward, raising the possibility that they have no

understanding of this simple causal relationship

The above experiments: String-pulling paradigm with variations,

Povinelli’s paradigm with variations, and lid-lifting paradigm with variations,

led us to suspect that chimpanzees and elephants do not

think.

The “throw the net” signal of the dolphins of

Laguna

We are now in the process of studying another candidate

for thinking in the animal kingdom: the bottlenose dolphin. To do this, we reluctantly let go of the

experimental option and conducted preliminary observations of a striking (and

beautiful) behavioral sequence: the

human-dolphin fishing cooperative in Laguna, Santa Catarina, Brazil (Pryor et

al., Marine

Mammal Science 6:77–82; Simões-Lopes, 1991, Biotemas, 4: 83-94).

| A Dolphin in Regular Motion | A Dolphin Asking for a Net |

|

|

The Signal and subsequent dive

|

|

|

|

|

As can be seen in the following video, the dolphins of

the Southern coast of Brazil herd fish towards a line of throw-net

fishermen. At a certain point, the

dolphin signals to the fishermen to cast their net. To my knowledge, the signal is unique,

not seen elsewhere in the behavioral repertoire of this animal.

A detailed motion analysis suggests that the signal is

short (mean time that any body part is seen above water while signaling: =1.4

seconds) and fairly uniform across individuals. (videos).

Our question, as before: Do the dolphins understand what they are

doing or was the behavior acquired through mindless trial-and-error

learning? We have here,

undoubtedly, a culture, if we accept Whitehead and Rendell’s definition of

culture, but to us, the critical question is not the existence of culture in

this limited sense. Rather, it

is: Is this a mindless or a

thinking culture? We hope to

provide a more definite answer to this question when we finish analyzing our

extensive video collection.

In this presentation, we’ve tried to contrast two ways

of seeing the world, two paradigms, which, in their turn, create strikingly

different ways of looking at our animal companions on this planet, something

like the famous Young Lady and the Hag.

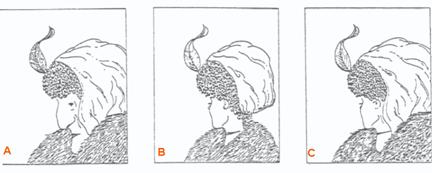

An

illustration of a Gestalt shift (A=hag; B=young lady; C=young lady and the

hag)

These contrasting paradigms are not mere semantic

quibbles, but they entail profound effects on our way of practicing

ethology. Here we shall only

provide four illustrations of these effects:

Training of animals: The two

models—thinking vs. trial-and-error—lead to radically different training

regimes. (We may note in passing

that all animal trainers we know operate as if the trial-and-error model is the

correct one).

Animal “cultures”: Culture claims include Japanese macaques, bottlenose

dolphins (Shark Bait sponges, signal to fishermen in Laguna), Whitehead’s sperm

whales, chimpanzees nut cracking, and others. The transmission of behavioral patterns

across generations is undeniable, but, if only trial-and-error learning

underlies this, if it is mindless, it is perhaps unwise to talk about “culture”

in such cases. At least until the

issue is resolved, we should let go of the word “culture” and talk instead about

something like “social learning.”

The ongoing debate on whether primates are cognitively

special. There is a growing body of experimental

evidence from cetaceans, elephants, dogs, corvids, parrots—perhaps even geese,

fish, bees, and ants—that they too deserve a place in the rising cognitive

sun. Again, the two paradigms lead

to radically new ways of interpreting such claims. According to the thinking paradigm,

these animals are the cognitive equivalent of primates; that is, parrots may be

as smart as chimpanzees. According

to the trial-and-error paradigm, the claim of equality still holds, but for

different reasons: If no animal

thinks, then all animals are equally (un)intelligent.

Limited expression of new behavioral

traits. The coordinator of my workshop, Dr.

Zhanna Reznikova, has just

noted that culture and social learning are often restricted to a few members of

a population, e.g., not all members of the snow monkey population wash or salt

potatoes, not all bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay use sponges; not all

bottlenose dolphins in Laguna cooperate with fishermen. Such observations are scarcely

reconcilable with the thinking hypothesis, but they are implied by the

non-thinking hypothesis.

Everyday Encounters: e.g., an eating dog attacking its scratching paw

(video); the familiar scene of a dog on a leash wrapped around a tree and unable

to extricate itself; chimpanzees losing their hands in the wild because they are

unable to figure out an exceedingly simple trap mechanism. For cognitive ethologists and lay

people, these are disturbing puzzles.

By contrast, the non-thinking camp expects blind genes and mindless

learning to produce at times such behavioral cul-de-sacs.

In our view, the question of

animal intelligence is an open one.

Science is not religion, and we should not adopt a particular viewpoint

simply because we find it agreeable or intuitively compelling. To find out whether a construct like

“cognitive ethology” is valid in the real world, we should refrain from exalting

and eulogizing animals, from directing all our energies to one side of this

question, from resenting the view and blocking the publications of those who

remind us that the animals may not think.

the moment, ethology needs a more cautious attitude to the question of

animal intelligence, and it needs to develop a catalog of animal

stupidities. Whenever possible,

ethologists need to apply Fabre’s falsificationist approach to any given situation, before

attributing thinking, insight, theory of mind, or culture to animals.

Conclusions:

1.

After

millennia of interactions with animals, we do not have a single, clearcut

example of thinking or understanding in animals. This by itself should give pause to the

cognitive ethology avalanche.

2.

The

larger brain of some animals serves many useful functions, e.g., improved

learning ability, but not necessarily thinking or understanding. There is, nowhere, neurological evidence

that animals think.

3.

The

founder of ethology, a great observer and a brilliant experimenter, and still

the greatest ethologist of them all, J. Henri Fabre,

is, at times, not even mentioned in animal behavior textbooks. Possible reasons: A Frenchman (the contemporary world of

science is dominated by the politically ascendant English-speakers), low-class

origins (likewise, we still talk about Darwinism, but the real priority

to the idea of natural selection belongs to the working class Wallace), an

unfortunate disposition in the social sciences to take premature theories too

seriously and to look askance at great experimenters, beautiful writing style,

mocking critiques of the venerable Erasmus Darwin and others who jumped to the

conclusion that insects and other animals think. His experimental manipulations still

present us with the best hope for resolving the question of animal

thinking.

4. The subject of animal thinking is open, and the paradigm shift in ethology towards thinking is unwarranted yet: We must think it possible that animals do not think.

5. We need a

catalog of animal stupidities (e.g., similar to an extant catalog on

deceptions).

6. In any given experiment, before concluding that thinking, or planning, or anticipation, or culture, or anything like that are involved, remove your caterpillar from the tunnel (or . . . tie your elephant to a post, place your lid on the ground, place a bucket on your head).

![]()